I had a lot of fun running the @WeAreDisabled rocur Twitter account for a week. I definitely recommend signing up even if, like me, you are on the fence about whether you ‘technically’ qualify as disabled. Chronic illnesses definitely count!

Talking book disposal on RNZ

Yesterday I went on Jesse Mulligan’s radio show to give some ideas about what to do with books you’ve decided to give away. Well that was what I intended to do. I ended up calling Fifty Shades of Grey the tinned tomatoes of books and outing myself as having developed a terrible crush on The English Patient live on air to the whole country, but there you go.

Review: Guardian Māia

This review was commissioned and published by Stuff in April 2019.

Your name is Māia.

You are a kaitiaki, although you're not sure yet of what or whom. You are a skilled fighter and speak the language of birds. You are in the bush when you encounter mangā – ferocious humanoid monsters named after the barracouta fish they resemble. Do you draw your patu to fight the mangā ,or leg it back to the pā to warn the rest of your iwi?

Interactive fiction is a relatively new form of digital storytelling, like a cross between an e-book and a computer game. The reader (or player) makes a series of choices that affect the narrative outcomes and the development of the point-of-view character. Imagine those old pick-a-path books for kids, but published as an app, rather than in print.

Interactive fiction is often solely text-based, but Guardian Māia, the first such work to be set in te ao Māori, benefits from more video-gamey elements, as seen in the visual and sound design. Each page has illustrated borders that reflect Māia's current environment, drawing on recognisably Māori designs and each new chapter begins with a full-page illustration. I found the sounds of native birdsong and traditional Māori musical instruments particularly evocative.

As you play through the narrative, you learn that Māia's iwi in Fiordland are being terrorised by a taniwha named Moko who demands young wāhine as tribute. Gradually more of the world is revealed as you explore. The environment seems both familiar and strange: here are the wildlife and atua of Aotearoa, but something isn't right. The land seems… odd.

One of my pet peeves with interactive fiction is that you often can't go back and make different choices without completely restarting. Guardian Māia has an elegant in-world solution to this: if your choices end up with, for example, the mangā killing you, you can negotiate with Hine-nui-te-pō in the land of the dead to return to various previous points. If, like me, you were the kind of child who used to read through the whole pick-a-path book in order to reverse engineer the "correct" ending, this is extremely satisfying.

Guardian Māia is an excellent work of Māori speculative fiction. It is written in English with frequent use of Māori words. If you come across one you don't know, you can just tap on it and a definition will pop up. The narrative is engaging, and I found Moko genuinely frightening as the story's antagonist. The characterisation of Māia is up to you – her health and mana increase and decrease according to the choices you make. There are three possible endings.

Guardian Māia is the first episode of a larger, planned story from Metia Interactive, an Auckland studio that has won various awards including the United Nations World Summit Award for Cube. Episode one is free, and is up now on Google Play and the iTunes App Store. Guardian Māia is not one for the littlies, but I recommend it for teens and anyone old enough to remember pick-a-path books.

Talking about disabled NZ writers on RNZ

Just before my essay on disabled NZ writers was published, I went on RNZ Afternoons to talk about what I found out.

Talking summer reading on RNZ

Over the break I went onto Lynn Freeman’s Summer Times show to have a chat about summer reads, particularly what we think an ‘easy read’ is and how that might be sexist (spoiler: it’s definitely sexist).

Talking book reviewing on RNZ

Today Jesse Mulligan and I had a chat about book reviewing in Aotearoa — after getting slightly distracted by which TV show has the best theme song (clearly Jem and the Holograms).

Te Manu Rongonui o Te Tau - Bird of the Year 2018

Bird of the Year is a really important time in Aotearoa’s political calendar: someone has to hold these manu māori to account. That someone is me.

Book review: The Rules of Magic, by Alice Hoffman

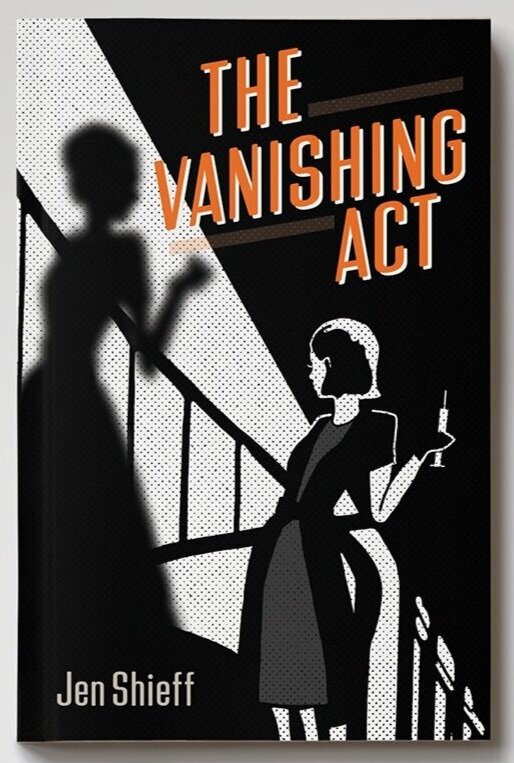

Book review: The Vanishing Act

This review was originally commissioned by the New Zealand Listener.

The Vanishing Act is a murder mystery set in 1960s Auckland. Glamorous Rosemary, who is gay, has been forced by homophobic parents to emigrate to Aotearoa. There she meets Rita, a lesbian who owns a brothel called The Gentlemen’s Club (also the title of Jen Shieff’s first book, for which The Vanishing Act is a standalone sequel). Soon a local doctor turns up dead, and scandalous intrigues ensue.

Initially The Vanishing Act feels like a bit of a mess. Several characters are introduced very quickly in very short chapters (sometimes only a page or so long), each of which is headed with a specific date. This requires the reader to flick back and forth to remind themselves who’s who and how the chronology fits together, which is annoying.

But it’s worth sticking around. Some of the characters are so unlikeable that seeing them get their comeuppance is deeply gratifying. The murder victim, George, is a villainous sex pest, and practically anyone could have killed him. The Vanishing Act will be enjoyed by lovers of the Yeah Noir genre (Kiwi crime), particularly those who are weary of the tropes of the troubled white male detective as the protagonist, and an abused woman as the murder victim.

Another strength of The Vanishing Act is as a work of historical fiction. Shieff has really done her research, and the novel wears this hard work lightly, making the setting seem natural rather than laboured. Shieff handles the mystery well and, although the resolution is a bit of stretch, it does keep the reader guessing. Once you get a handle on who’s who, The Vanishing Act is an entertaining read.

Professional rat art

Robot Hugs is one of my favourite web comic artists. One day on Twitter they offered to draw some sketches of people’s pets, so I sent in a photo of my pet rat Valentina and they drew me this. I LOVE IT.

Valentina, by Robot Hugs. CC BY-NC 4.0

Book review: The New Ships

This review was originally published in The Reader in July 2018.

This book is just superb. Kate Duignan’s The New Ships is a novel set mostly in Wellington about Peter Collie, whose wife Moira has just died, and his relationship with their son Aaron. Aaron is biologically Moira’s but not Peter’s, although the two of them have raised him since birth. A lot of the book is told in flashback, and we learn that Peter’s daughter from a previous relationship may or may not have died as a toddler. Part of the reason we don’t know is because Peter has chosen not to investigate. It’s a pretty huge thing to be uncertain about.

There are a lot of huge uncertainties in this novel, and I suspect it’s not a coincidence that the ‘present’ of the book is set in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. Peter and Moira are white but Aaron’s unknown birth father was a man of colour, and Aaron’s ethnic identity is another source of uncertainty that troubles Peter. Moira says he was conceived in Australia – might he be Aboriginal? As a child Aaron befriends some Māori and Pasifika kids and declares his ‘real’ dad is Rarotongan. When Aaron boards a plane for London after Moira’s funeral but doesn’t arrive there, Peter starts to panic. Airport security and Islamophobia are peaking, and Aaron is ethnically ambiguous enough to be mistaken for an Arab and labelled a terrorist.

One of the things I really like about The New Ships is that it’s easy to read and also full: of ideas, of story layers, of exceptional writing. Here are a few sentences that I particularly loved: when describing a sailor Peter admires: ‘I’d trust this man to put down a dog I was fond of.’ At the tail end of a family holiday when Peter just wants to go home: ‘I was sick of … sitting like a damp, agitated ghoul at my wife’s side.’ When Peter is facing his first Christmas after Moira’s death: ‘It’s intolerable, summer ahead, all the days fat with beauty, useless.’

Peter is a flawed protagonist. We are in his head the whole way through the book so our sympathies naturally flow towards him, but there’s no denying he’s done some pretty dodgy stuff. Why doesn’t he lift a finger to find out for sure whether his daughter is alive or dead? There’s also a very uncomfortable narrative thread wherein Peter, who is middle-aged and a partner at his law firm, sifts onto a young, attractive female intern while trying to convince himself that he’s “helping” her. I found his behaviour distressing, especially in light of the real-life stories about the way female law interns are treated here.

Duignan resolves some of the uncertainties in The New Ships but not all of them, giving the reader a pleasing sense of narrative satisfaction without anything feeling pat or contrived. I highly recommend The New Ships to lovers of NZ fiction and of good books in general.

Review by Elizabeth Heritage

The New Ships

by Kate Duignan

Published by VUP

ISBN 9781776561889

Talking NZ comics on RNZ

Today I had a yarn with Jesse Mulligan on RNZ Afternoons about ngā pakiwaituhi o Aotearoa, NZ comics.

If I’m perfectly honest it was all a ruse to have an excuse to talk about my pet rat Albus who was filmed for Tragicomic, a web comic slash web series by The Candle Wasters. Go Albus!

Lack of gender diversity in NZ kids' books

Book review: Feel Free

This review was commissioned and published by the New Zealand Listener in May 2018.

In the foreword to her collection of essays, Feel Free, Zadie Smith starts with her anxiety about this artform. “It’s true that for years I’ve been … wondering if I’ve made myself ludicrous … Essays about one person’s affective experience have, by their very nature, not a leg to stand on. All they have is their freedom.” Including the freedom to be of wildly varying quality.

Smith’s insecurity pulses throughout the book. A lot of the essays in Feel Free are works of criticism: of books, films, and artworks. Some are the texts of talks Smith has given, often while receiving awards for her writing. Some are personal essays reflecting on Smith’s life as a woman who grew up poor in North London with a black mother and a white father, and who is now a successful middle-class writer teaching on a prestigious MFA course in the US, and what that transition means. As with Smith’s novels, themes of immigration, racism, multi-culturalism, and feminism abound.

The essays I liked the best – and at her best Smith is truly excellent – were the ones where she addresses a central uncertainty that is worrying her. In “The I Who Is Not Me” Smith considers why she avoided writing fiction in the first person until her latest novel, Swing Time, whose protagonist’s life in some ways resembles Smith’s own. “It became important for me to believe my fiction was about other people, rather than myself, I took a strange pride in this idea, as if it proved I was less self-preoccupied or vain than the memoirist or the blogger or the Bildungsroman-er. No one could accuse me of hubris if I wasn’t there.” But then Smith is inspired by Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint: “By saying ‘I’ in a certain mode, an ambivalent, fictional mode, Roth made possible through Portnoy a new kind of ‘I’ in the world, a gift of freedom … The offer was not: You, too, can be like Portnoy. The offer was: Portnoy exists! Be as you please.”

The essays I liked the least were the ones where Smith seems to be trying to cover up her insecurity with intellectualism. From an exhibition review: “For us, the image-map that has been made of the world is not exactly the same as the territory itself, or rather, we can still remember — if only vaguely — a moment in time when the seams were still partially visible.” When Smith writes in this impersonal, academic style, often leaning towards pomposity, I found my interest waning.

My favourite kinds of book reviews to read are enthusiastic ones, where the reviewer dives headlong into a work they admire and holds up to the light all their favourite parts to share. Smith reviews the Patrick Melrose novels by Edward St Aubyn: “Writing reviews, you spend quite a lot of your time typing out the sentences of other people, i.e. quoting. Usually this is dull work; with St Aubyn, it’s a joy. Oh the semicolons, the discipline! Those commas so perfectly placed, so rhythmic, creating sentences loaded and blessed, almost o’erbrimmed, and yet sturdy, never in danger of collapse. It’s like fingering a beautiful swatch of brocade.”

The essays in Feel Free get much better as the book progresses, so I recommend starting at the back. Overall the book feels more like a compilation of all the non-fiction Smith happens to have written over the past few years, rather than a curated collection of her best essays. But the best bits of Feel Free are worth reading in order to spend time with Smith when she’s being vulnerable and honest. “I feel this – do you?”

Talking interactive fiction on RNZ

Today I went on Jesse Mulligan’s RNZ Afternoons programme to talk about interactive fiction. As with so many things, the internet has given IF a huge boost, and there are a vast range of works to choose from — way more than the pick-a-path books you had when you were a kid!

Orville's book award

Book review: When They Call You A Terrorist

WHEN THEY CALL YOU A TERRORIST: A Black Lives Matter Memoir, by Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Asha Bandele (Canongate/Allen & Unwin, $25)

This article was first published in the April 7, 2018 issue of the New Zealand Listener.

Patrisse Khan-Cullors, co-founder of Black Lives Matter, grew up “between the twin terrors of poverty and the police”.

Although only 257 pages long, this Black Lives Matter memoir is a big, big book. Co-written with journalist Asha Bandele, When They Call You a Terrorist is mostly the story of Patrisse Khan-Cullors’ life. The final quarter of the book is devoted to a history of the Black Lives Matter movement, of which she is a co-founder.

Khan-Cullors is a black woman, “a mother and a wife, a community organizer and queer, an artist and a dreamer” from Los Angeles. She grew up “between the twin terrors of poverty and the police”, who threatened black children and routinely tortured black adults. But this is no sob story: Khan-Cullors is one of those extraordinary people able to transform anger and grief into effective action.

As well as her experience of state violence, she’s motivated by the history of anti-racism campaigning in the US. “The stories I learnt as a small girl who read about civil rights, black power and black culture flowed everywhere in me and through me.”

Her personal narrative is backed up by startling statistics: in California alone, “a human being is killed by a police officer roughly every 72 hours” and “63% of these people killed by police are black or Latinx. Black people, 6% of the California population, are targeted and killed at five times the rate of whites.”

The odds are stacked against all people of colour in the US, especially under the present Administration, but Khan-Cullors brings to light the special hatred and fear that white-supremacist Americans have for black Americans in particular. She draws a direct line from slavery to Jim Crow to today’s epidemic of mass incarceration and institutionalised police brutality. “We have to talk very specifically about the anti-black racism that stalks us until it kills us … There is something quite basic that has to be addressed in the culture, in the hearts and minds of people who have benefited from, and were raised up on, the notion that black people are not fully human.”

Khan-Cullors is clear about what needs to be done – and is doing it. “The goal is freedom. The goal is to live beyond fear. The goal is to end the occupation of our bodies and souls by the agents of a larger American culture that demonstrates daily how we don’t matter … And I know that if we do what we are called to do … we will win.”

Black Lives Matter is an explicitly feminist movement founded by black women that seeks to engage queer, trans and disabled black women in particular. Among their guiding principles are: “Being self-reflective about and dismantling cisgender privilege and uplifting black trans folk … Asserting the fact that Black Lives Matter, all black lives, regardless of … ability [or] disability … Fostering a trans- and queer-affirming network … freeing ourselves from the tight grip of heteronormative thinking …”

Founded in 2013, it’s having an ongoing effect. “We have created space for us to finally be unapologetic about who we are and what we need to be actually free, not partially free. … We make everyday people feel part of a push for change.”

Reading this memoir put me in awe of the exceptional strength and compassion that US anti-racism campaigners must possess to face up to the scale of the problem and make positive changes. Although this book is about the US, it made me look at race relations here in Aotearoa with new eyes. When They Call You a Terrorist will stay with you for a long time.

Book review: Chaucer's People

This review was commissioned by and published in the New Zealand Listener in February 2018.

To enjoy this book fully, I recommend pretending it’s being read to you by Maggie Smith when she’s playing her Downton Abbey character Violet Crawley.

Chaucer’s People, like Violet, takes no prisoners and surges forward at all times with a serene sense of its own rightness. It’s nominally a medieval social history centred around The Canterbury Tales, a long poem about pilgrims travelling to Canterbury written by Geoffrey Chaucer in the 14th century. If you don’t already know and love the Tales, and have a solid grounding in medieval European history, this is not the book for you. Author Liza Picard refuses to stop for beginners.

From almost the first page, I fell for Picard’s Violet-like charm. Here’s the opening sentence of the chapter on the Wife of Bath: “She really came from ‘beside Bath’, probably one of the Cotswold villages, not Bath itself, but she has gone down in history as the Wife of Bath, and it seems pointless to correct her address now.” And from later that same page: “Hose are always shown in contemporary pictures as smoothly encasing the leg, which I assumed was an artistic licence until I caught sight of a modern young woman whose jeans were tighter than skin-tight, and certainly encased her legs smoothly, leaving little room for wrinkles.”

Chaucer’s People is an idiosyncratic history. It eschews any kind of academic authority or appeal to popularity in favour of a brisk trot through those parts of medieval English life that Picard happens to find personally interesting. In different hands this could have been dire, but Picard brings her eye for intriguing detail to bear with great effect. In an interview with The Guardian, she said: “I am not a properly trained historian. I am a lawyer by trade, and an inquisitive, practical woman by character.” She writes, she says, to please herself, and focusses on primary sources rather than other people’s research.

The result is a compendium of interesting tidbits. Chaucer’s People is grouped loosely around the different characters in the Tales to provide a much-needed framing structure, although even so Picard repeats herself a few times. This is not a book to be read in one sitting, but rather to be dipped in and out of. In the chapter on the Cook, Picard gives us several pages of medieval recipes. “I have tried to keep the feeling of the language … Medieval English used the word ‘him’ for he, she, it and them. The recurrent command to ‘smite him in gobbets’ is so much more vivid than ‘cut it into bite-sized pieces’ that I’ve let it stand.”

Chaucer’s People has, perhaps, a niche audience. But if you can find someone who’s studied the Tales and has a soft spot for English eccentrics, they will love every single page.

Book review: The Maid's Room by Fiona Mitchell

This review was commissioned by and originally published in the NZ Herald in December 2017.

The Maid’s Room is the story of Tala and her sister Dolly, Filipina women who have left their families behind to work in Singapore as maids. Their working conditions are atrocious: they are kept in wage slavery and bullied. The threat of deportation is constant. Tala and Dolly are intimately involved in their employers’ lives – living in their houses and raising their children – but are treated as less than human.

The tipping point for Tala comes when her employer tries to hide a camera in her room in order to spy on her. Enraged, she starts a blog to let the world know the truth about maids’ working lives, and it is the fallout from this that drives the plot. “Her friends call her ‘the rescuer’ … she knows how to play the system, to speak up and out.” A lot of the story is told from Tala’s point of view, and she’s a great character to spend time with: loud, loyal, and brave. I was rooting for her the whole way through.

If this is starting to sound like The Help by Kathryn Stockett, that’s because it is. (The Help is a novel and film set in the Southern US in the 1960s, in which a white journalist exposes the realities of the working lives of poor black maids.) British author Fiona Mitchell credits The Help as the inspiration for The Maid’s Room, and references it throughout her novel.

And this is where it gets tricky. The Help has rightly been criticised for being a white saviour fantasy that centres white feelings at the expense of the black experience. In her response to the film of The Help, US critic Roxane Gay says: “That question [of writing across difference] becomes even more critical when we try to get race right, when we try to find authentic ways of imagining and re-imagining the lives of people with different cultural backgrounds … I don’t expect writers to always get difference right but I do expect writers to make a credible effort.”

So – did Mitchell (a white writer) get difference right? And if not, did she make a credible effort? It’s up to Filipina critics to answer the first one. On the second question: hmm.

Mitchell lived in Singapore for a couple of years and interviewed some Filipina maids there, so she is writing at least partly from primary research. One positive difference from The Help is that Mitchell has Tala publish her own work, rather than having a white women write it for her. But there’s a very telling scene in The Maid’s Room where some of the employer characters read The Help in their book club. Their reactions vary from those who can see the parallels to their own situation to the more overtly racist characters who can’t. No one – not even the character Mitchell says is based on herself – asks the maids what they think, or questions a white woman’s right to tell the stories of women of colour.

I get the feeling that Mitchell has absorbed the lesson that racism is bad, but has yet to learn how to avoid cultural appropriation (Gay’s ‘credible effort’) or to question her own privilege. In her author’s note, Mitchell displays a damning lack of self-awareness by directly comparing the racism faced by Filipina maids to her own experience in London as the daughter of an Irish man. Although The Maid’s Room doesn’t replicate the missteps of The Help to the same degree, it suffers from the same aura of white saviour fantasy. This debut novel is one to avoid.